I took my mother to see “Saving Mr. Banks” after Christmas. We enjoyed it. It was a well-done adult Disney movie. (I wouldn’t recommend it for children.) We’re both interested in the creative process so a movie about making a movie didn’t seem too masturbatory. It was interesting to consider how P.L. Travers’ reservations about Walt Disney making “Mary Poppins” impacted the final project. And it was enlightening to me that the “Let’s Go Fly a Kite” ending was born not of an idyllic childhood but of a troubled and conflicted relationship with fathers, both Disney’s and Travers’.

My mother and I hadn’t seen a movie together in a theater since “The Sound of Music.” We almost didn’t see that. She read a blurb in the paper that indicated it was about a “young prostitute.” Later she read another that described Maria as a “young postulant” and chided herself for misreading the word. Knowing my mother and her voracious reading habits, I doubt she mistook “postulant” for “prostitute.” I suspect a typo in the first blurb.

We recalled how we had seen “Mary Poppins” at a matinee together with my younger brother and sister in the summer of 1965. We liked it so much we stayed to watch it again. We forgot about (and I missed) my ballgame that evening. That was not easy to live down with my teammates. Missing a game for “Goldfinger,” maybe, but “Mary Poppins” was definitely not cool. I wasn’t permitted to see movies like “Goldfinger.” I didn’t tell my teammates how I spent my time viewing the movie the second time. Almost fifty years later I didn’t tell my mother either.

I was young enough that I still couldn’t predict a storyline. The first time through I thought the movie was ending when Bert and Mary and Jane and Michael looked out over the city after climbing the stairs made of smoke. All movies ended too soon to my childish mind. I did feel the pathos of Mr. Banks’ situation and rejoice at his redemption once I saw it. I just had no idea that it was coming. Of course, “Saving Mr. Banks” informed me that his redemption was a late idea anyway.

What troubled me the second time through the film was Mary Poppins’ righteous indignation over the children’s concern that she had been “sacked.” I didn’t know what “sacked” meant, but could glean from the context that it had something to do with losing her job. But her reaction seemed too over-the-top for something so trifling. (I was eleven.) Before the movie ended the second time, I had satisfied myself with a definition for “sacked” that included Mary Poppins, naked, tied spread-eagle between the pillars in the entry foyer of the Banks’ home, and soundly whipped by Mr. Banks with a buggy whip. That seemed sufficient to justify her reaction.

I laughed rather inappropriately a decade or so later watching the “The Story of O,” when the door at the top of the stairs opened to reveal the scene I had imagined as a child. O had recreated it with the maid to educate a young man who wanted to rescue her from her slavery. He gazed from her sweaty beaten body to the inexplicable look of her face. The disheveled maid regarded him as an unwelcome intruder. Obviously, she would resume beating O the moment he left. This “harsh reality” was just too much for O’s would-be rescuer, so he fled.

I thought I might be dragged off in handcuffs from the Fine Arts Theater for watching “The Story of O.” I thought maybe I deserved to be arrested and charged with something for enjoying it so much. And I felt like that every time I saw it. I saw it three different times with three different male friends. But I was the only one who got it. I knew something at twenty-two I didn’t know at eleven. I didn’t want to beat O, necessarily, I wanted to be her. We shared an intimate secret by then courtesy of my highschool girlfriend; namely, that we could be whipped into a euphoric state of submission.

O was the fictional creation of French author Anne Desclos, a.k.a. Dominique Aury, a.k.a. Pauline Réage. She wrote it for her married lover, twenty-three years her senior. “I wrote it alone, for him, to interest him, to please him, to occupy him….I wasn’t young, I wasn’t pretty, it was necessary to find other weapons…The physical side wasn’t enough. The weapons, alas, were in the head….You’re always looking for ways to make it go on….The story of Scheherazade,[1] more or less.”[2] Histoire d’O, its title in French, was first published in 1954.[3]

“The author said later,” according to Carmela Ciuraru,[4] “that Story of O, written when she was forty-seven, was based on her own fantasies…Some twenty years after the book came out, she admitted that her own joys and sorrows had informed it, but she had no idea just how much, and did not care to analyze anything. ‘Story of O is a fairy tale for another world,’ she said, ‘a world where some part of me lived for a long time, a world that no longer exists except between the covers of a book.’” Earlier, she had quoted the author, “‘By my makeup and temperament I wasn’t really prey to physical desires…Everything happened in my head.’”[5]

Ms. Ciuraru also quoted Susan Sontag, “the first major writer to recognize the novel’s merit and to defend it as a significant literary work….In her 1969 essay ‘The Pornographic Imagination,’ Sontag…compared sexual obsession (as expressed by Réage) with religious obsession: two sides of the same coin. ‘Religion is probably, after sex, the second oldest resource which human beings have available to them for blowing their minds,’ she wrote.”

I can’t help but see the relationship to πορνεία[6] here as Ms. Ciuraru continued to highlight Sontag’s contribution: “In her disciplined effort toward transcendence, O is not unlike a zealot giving herself to God. O’s devotion to the task at hand takes the form of what might be described as spiritual fervor. She loses herself entirely…”[7] Then she connected this kind of πορνεία to death.

“If O is willing to sustain her devotion all the way through to her own destruction, so be it. She wants to be ‘possessed, utterly possessed, to the point of death,’ to the point that her body and mind are no longer her responsibility.”[8] I’ve not read the book, and this particular concept of possession was not clear to me from the movie I saw almost forty years ago. One of the friends who saw it with me had a more filmic eye than mine and recognized the genre as horror, a monster movie. Then I saw it as a tale of a damsel in distress who became a monster.

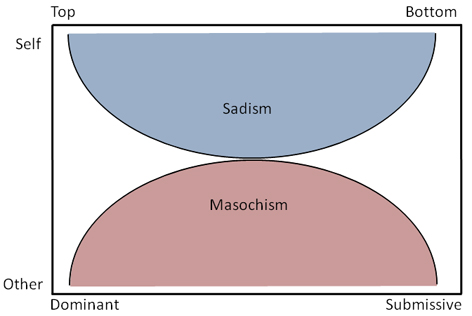

As O questioned whether her master could or would endure for her what she had endured for him, she branded him with an ‘O’ from a hot cigarette holder. (She had been branded for him earlier in the film.) She was both dominant and submissive, top and bottom, and I would be hard-pressed to decide if she was more masochistic or sadistic by my own understanding of the terms (fig. 4).

But in the above description—“She wants to be ‘possessed, utterly possessed, to the point of death,’ to the point that her body and mind are no longer her responsibility”—I perceive some insight from “The Story of O” into πορνεία as an ancient religion of the flesh, primarily as ironic contrast to being led by the Spirit.

Writing to the Corinthians about ancient Israel at Sinai, Paul said, God was not pleased with most of them, for they were cut down in the wilderness. These things happened as examples for us, so that we will not crave evil things as they did. So do not be idolaters, as some of them were. As it is written, “The people sat down to eat and drink and rose up to play.” And let us not be immoral (πορνεύωμεν, a form of πορνεύω),[9] as some of them were (ἐπόρνευσαν, a form of πορνεύω), and twenty-three thousand died in a single day.[10] Paul was fairly explicit here that the Israelites’ play to celebrate the golden calf was πορνεία, the noun which signifies what those who engage in πορνεύω do.

In college, the second time after I gave up writing “The Tripartite Rationality Index,” I read “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, by B.Z. Goldberg[11] (the pen name of Benjamin Waife). Goldberg, a journalist and managing editor of the Yiddish “the Day…found time to research in the field of psychology of religion” as he wrote a daily column on foreign affairs. Of Baal, he wrote:

Baal was the one great abstract god of antiquity.[12]

On the summit of every hill and under every green tree Baal is worshipped—the god whom people knew long before they had heard of Jehovah, the divinity whom they loved long after they had learned of the one and true God.[13]

Baal was the greatest god of all, but what was Baal? How could one fathom this infinite mystery? Primitive man, limited in his thinking and circumscribed in his imagery, sought a concrete form for the mightiest of the gods. So he looked into the mirror of life and in the image of what he saw therein he created his Baal.[14]

The consummation, if you will, of this man-made religion, according to Goldberg, is “in the union of the sexes.”[15]

The songs grow wilder, the contortions of the bodies more frenzied, while the drum and the flute fill the air with passionate tones that steal into the hungry hearts of dancer and worshipper. The dances break up in chaotic revelry. Priestess and worshipper join in the merry-making. Tired, drunk, half-swooning, the dancer is still conscious of one thing: somebody will touch her navel—she must follow—but the coin; he must first give her a coin, the coin that is sacred to Baal. As she is trying to seat herself, hardly able to stand upon her feet, a worshipper touches her. She rises as if awakened from sleep. She follows him blindly into a tent, where both priestess and worshipper consummate the final crying prayer to Baal, the prayer of love.[16]

The instructor who employed me as a TA was a neo-pagan, a witch in his own words, who worshipped Celtic Baal. The ligature marks on his wrists after a Samhain[17] celebration alerted me that πορνεία might be kinkier than Goldberg let on. I didn’t call it πορνεία yet. I only saw the relationship to ancient Israelite religion in the Old Testament.

O as a slave was naked. When worshippers “entered the most sacred chamber and faced the statue of Baal, they would have to present themselves naked before their god.”[18] (“Only a few laymen ever entered this vestibule, the holy of holies of the great god.”)[19] Though the translations are disputed by the translators of the NET, the sight Moses witnessed according to the King James translators was that the people were naked; (for Aaron had made them naked unto their shame among their enemies).[20] Or as John Nelson Darby (known as the father of Dispensationalism[21]) translated the verse: And Moses saw the people how they were stripped; for Aaron had stripped them to [their] shame before their adversaries.[22]

So in contradistinction to the nakedness of πορνεία as a religion of the flesh, God said, And you must not go up by steps to my altar, so that your nakedness is not exposed.[23] Beyond that He told Moses to make undergarments for the priests to cover their naked bodies; they must cover from the waist to the thighs.[24] Consider Leviticus 18:6-18 (NKJV) in this context:

None of you shall approach anyone who is near of kin to him, to uncover his nakedness: I am the Lord [Table].

The nakedness of your father or the nakedness of your mother you shall not uncover. She is your mother; you shall not uncover her nakedness [Table].

The nakedness of your father’s wife you shall not uncover; it is your father’s nakedness. [Table]

The nakedness of your sister, the daughter of your father, or the daughter of your mother, whether born at home or elsewhere, their nakedness you shall not uncover [Table].

The nakedness of your son’s daughter or your daughter’s daughter, their nakedness you shall not uncover; for theirs is your own nakedness [Table].

The nakedness of your father’s wife’s daughter, begotten by your father—she is your sister—you shall not uncover her nakedness [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of your father’s sister; she is near of kin to your father [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of your mother’s sister, for she is near of kin to your mother [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of your father’s brother. You shall not approach his wife; she is your aunt [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of your daughter-in-law—she is your son’s wife—you shall not uncover her nakedness [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of your brother’s wife; it is your brother’s nakedness [Table].

You shall not uncover the nakedness of a woman and her daughter, nor shall you take her son’s daughter or her daughter’s daughter, to uncover her nakedness. They are near of kin to her. It is wickedness [Table].

Nor shall you take a woman as a rival to her sister, to uncover her nakedness while the other is alive [Table].

The note in the NET claimed that to uncover nakedness “is clearly euphemistic for sexual intercourse,” and the translators translated the phrase have sexual intercourse. They may be correct. Consider, Nor shall you take a woman as a rival to her sister, to uncover her nakedness while the other is alive. But the more literal translation seems pointedly addressed to familial Baal worship.

For the submissive masochist, however, nudity is the preferred state of being. Even the humiliation of nakedness is a pleasure. The wrath of God…revealed from heaven,[25] as Paul described it was, God gave [those who exchanged the glory of the immortal God for an image resembling mortal human beings or birds or four-footed animals or reptiles[26]] over in the desires of their hearts to impurity, to dishonor their bodies among themselves.[27] Even in wrath there is mercy.

For the word of God is living and active and sharper than any double-edged sword, the writer of the letter to the Hebrews wrote, piercing even to the point of dividing soul from spirit, and joints from marrow; it is able to judge the desires and thoughts of the heart. And no creature is hidden from God, but everything is naked and exposed to the eyes of him to whom we must render an account.[28] The truth of this image, being naked and accountable to God, that so horrifies my religious mind, is warm, familiar and comforting to my masochism.

[2] “The Story of the Story of O,” Carmela Ciuraru, Guernica / A Magazine of Art & Politics http://www.guernicamag.com/features/ciuraru_6_15_11/

[5] “The Story of the Story of O,” Carmela Ciuraru, Guernica / A Magazine of Art & Politics http://www.guernicamag.com/features/ciuraru_6_15_11/

[7] “The Story of the Story of O,” Carmela Ciuraru, Guernica / A Magazine of Art & Politics http://www.guernicamag.com/features/ciuraru_6_15_11/

[8] “The Story of the Story of O,” Carmela Ciuraru, Guernica / A Magazine of Art & Politics http://www.guernicamag.com/features/ciuraru_6_15_11/

[12] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter I, p. 145 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[13] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter I, p. 144 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[14] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter I, p. 145 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[15] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter I, p. 147 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[16] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter IV, p. 158 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[18] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter III, p. 152 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[19] “The Sacred Fire, the story of sex in religion”, B.Z. Goldberg, (1930) Book II, Chapter IV, p. 154 http://www.sacred-texts.com/sex/tsf/tsf08.htm

[21] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xEGe8EzygwM In this YouTube clip a preacher condemned Darby to hell “according to the Bible” for modern biblical scholarship (deleting or changing words from the KJV). The verses cited in his sermon (1 John 5:7; Acts 8:37; Luke 2:33; Colossians 1:14) are annotated in the NET. Anyone can decide whether the arguments are valid or not. I’m only concerned when changes are made without including the argument in a footnote. I suppose my point here is that Darby and the translators of the KJV were in closer agreement with each other than with the translators of the NET.

[27] Romans 1:24 (NET) Table

Pingback: Adultery in the Law, Part 3 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: David’s Forgiveness, Part 5 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Romans, Part 2 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Sexual Immorality Revisited, Part 3 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Romans, Part 65 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Romans, Part 64 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: What is Sexual Immorality? | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Paul’s Religious Mind | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Conclusion | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Adultery in the Prophets, Part 3 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: My Reasons and My Reason, Part 3 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: My Reasons and My Reason, Part 1 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Adultery in the Prophets, Part 2 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: David’s Forgiveness, Part 2 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind

Pingback: Adultery in the Prophets, Part 1 | The Gospel and the Religious Mind